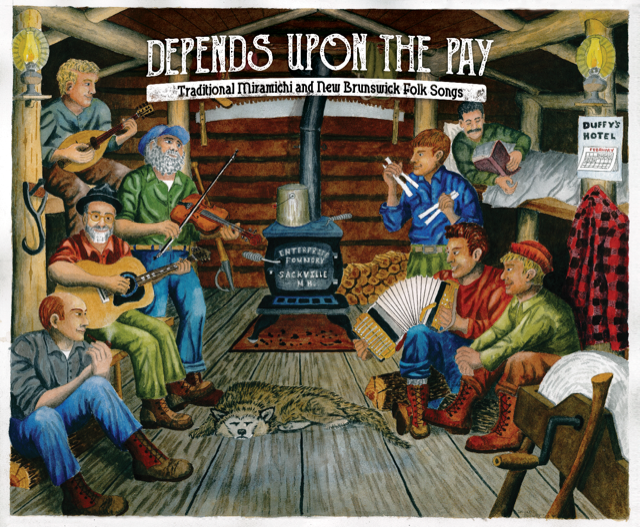

Fredericton musician Mike Bravener shares the fascinating backstory behind his forthcoming album, Depends Upon The Pay, a collection of New Brunswick folk music.

Matt Carter

Mike Bravener never saw himself as someone steeped in a folk tradition. Even though he spent the last few decades singing the songs of Elvis, Hank Williams, and Johnny Cash, along with his own songs influenced by these three and others, the roots of his connection to music directly inspired by folk traditions remained largely unidentified. But that all changed when a series of unrelated events helped him put everything in perspective.

In advance of his forthcoming album, Depends Upon The Pay, Bravener sat down with Grid City Magazine to trace the history behind this project and his newfound passion for traditional New Brunswick folk music.

“This all started maybe six or seven years ago while I was working at Chapters,” said Bravener. “I had befriended a guy named Harry Bagley. He was always talking books and I would tell him about music. He knew I was a musician and one day he came in and said, ‘New Brunswick folk music. That’s what you should be doing.’ I told him I didn‘t even know any Canadian folk music let alone folk music from New Brunswick.”

But the suggestion lingered and Bravener held on to it.

“These types of interactions don’t happen often in my life, so I thought maybe there is something to this,” he said.

About a year later he was given a pile of old records that contained a few collections of Canadian folk music.

“It was quite a collection of music. There were a bunch of jazz records and I put those right into my collection,” he said. “The folk stuff I decided to hang on to but still wasn’t ready to get into them just yet so I packed them away under the stairs.”

Skip ahead a few more years and folk music comes knocking for a third time when Bravener is offered a chance to take a job as an actor/musician at the King’s Landing Historical Settlement.

“The music I associated with King’s Landing was very Irish sounding and I turned down the offer because based on my experience and the music I had heard there in the past. I thought I wasn’t the right fit and would disappoint them,” he said. “I was more Johnny Cash, Elvis and Buddy Holly. But eventually they wrote to me again and asked if I’d reconsider. That made me think maybe Harry Bagley was on to something six of seven years ago. This is a music/acting gig that came looking for me.”

Bravener got the job and was assigned the role of a character named Abraham Munn, a historical figure born in 1858 and known for his documented work as a lumberman and a guide. Munn was also a musician and is credited for crafting the melody for a poem called Peter Emberley.

“That song is perhaps New Brunswick’s most famous traditional folk song from the 1800s,” said Bravener. “I had to learn that and another song Munn wrote about the Dungarvon Whooper. I also started sourcing lyrics to a bunch of other more Americana folk songs like Oh My Darling and Oh Suzanna and a few others that I kind of knew. At the time, I needed to build up a repertoire.”

Once he established his repertoire and began singing these songs to visitors at the historical settlement, Bravener began hearing from others who were either surprised to hear folk songs from the province or had a song of their own to share with him. Through this music he had made a connection with a new audience. At the same time and without realizing it, his passing interest in folk music was slowly becoming a passion.

Years prior, Bravener was a competitive Elvis impersonator. He had the outfits, the songs and all the mannerisms down. In a lot of ways, his days spent at the Heartbreak Hotel taught him more than just the music of one of rock and roll’s founding fathers. He learned a lot about acting and about doing research – two skills that proved to be vital additions to his ability as a musician working this new chapter in his performance career.

“When I got into the Elvis thing I really studied Elvis,” he said. “I watched movies and concert videos, I read everything I could, and I tried to find every recording or rehearsal tape that was out there. I just was passionate and excited about it. I wanted to become more believable in the Elvis world. So with folk music, I’ve never worked on a lumber camp in my life, so I had to learn as much as I possibly could. I dove right in.”

This personal research project led him to the work of provincial music archivists like Louise Manny and Helen Creighton and to collections of sound recordings published through major folk labels and others housed within the provincial archives. He also met direct descendants of many historical figures documented in New Brunswick folk music. Much like his deep dive into all things The King, Bravener began accumulating a vast amount of knowledge of both New Brunswick folk music and folk music history.

Recording an album became the next logical step. To make it happen, Bravener teamed up with members of the bluegrass/folk ensemble the Montgomery Street Band to rehearse and develop arrangements. When they were ready, the group spent three days in early 2020 at Outreach Productions recording each track live off the floor.

Depends Upon The Pay is authentic in sound and delivery. It’s as timeless as the music it contains. The pairing of Bravener and the MSB is ideal for such a collection, with voices and instruments perfectly capturing the sound and feel of the times.

The album’s 14 tracks span traditional, instrumental and acapella renditions of songs, some penned over 150 years ago, and are a testament to the timelessness of folk music.

Depends Upon The Pay comes out June 19 capping off the first chapter in Bravener’s unexpected journey through an area of music he never thought too much about.

“I never started out thinking I would be doing an album of traditional folk music,” said Bravener, who after combing through hundreds of songs for this project was surprised to see just how many of these songs still have a place in our culture today.

“A lot of these songs are still relevant today,” he said. “There are songs of heartache and all of the things that go with relationships. These songwriters were asking the questions that we’re still asking today. A lot of the songs from 1830, 1840 and 1850 could easily be from 2020. One of the things I’ve discovered from all this work is that we really haven’t changed that much.”

Mike Bravener WEB | BANDCAMP | TWITTER