Writer Claire Shiplett Travels to Eastport, Maine to Explore Janice Wright Cheney’s Latest Installation

Claire Shiplett | All photos supplied by Janice Wright Cheney

We enter the Free Will North Church through the basement, ascending the stairs and parting black lace curtains to be greeted by a partially renovated space with white vaulted ceiling and rows of dark pews. Lingering sunlight illuminates the stained glass windows, but above us new lights are shifting, flickering, shimmering. As it grows dark outside, the lights brighten, the shadows deepen, and a chorus of sound swells. Janice Wright Cheney’s Sardinia comes to life.

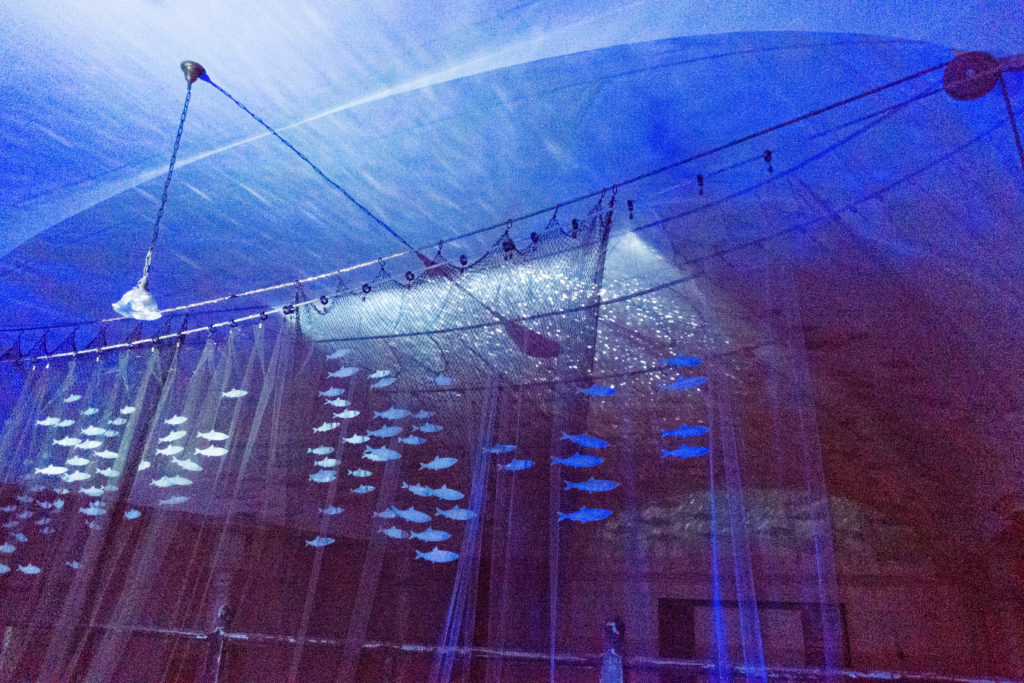

Fredericton-based artist Janice Wright Cheney’s most recent work is an immersive multi-media installation consisting of sound, video projection and sculpture that projects thousands of sardines onto the ceiling of the Free Will North Church in the once bustling cannery town of Eastport, Maine, recently dubbed “the little town that might”[1]. The images are projected on and through hung fishing nets and handmade sardine replicas that cast distorted shadows. Wright Cheney worked in collaboration to create the piece, incorporating film editing by Ryan O’Toole and an original sound composition by Charles Harding (Property//) and David Cheney. Sardinia was developed during Wright Cheney’s stay at the StudioWorks Artist-in-Residence Program, a program designed by Eastport residents Hugh French and Kristin McKinlay at the Tides Institute and Museum of Art. Wright Cheney, now joining a growing roster of StudioWorks alumni, invited me to visit Eastport and witness Sardinia in person.

My favorite moments of Sardinia occur when the sardines cease to be fish and morph into light and shadow that shoot across the ceiling in a cosmic stream. Wright Cheney was inspired by the writings of John Steinbeck, in particular his Cannery Row, set in the cannery town of Monterey, California. As he wrote in The Log from the Sea of Cortez, “a shimmering phosphorescence on the sea and the spinning planets and an expanding universe [are] all bound together by the elastic string of time. It is advisable to look from the tide pool to the stars and then back to the tide pool again.” Looking up at Sardinia, one feels that one is traveling through space, a mysterious beyond above that evokes the connectedness of the past and the present. An experience at once mesmerizing, calming and haunting. The stream lends transience to the fish – they are lights that pass by and disappear. These moments are juxtaposed with moments when the sardines are definitely bodies; the dense school gently converges to create a dark mass that blocks out the light. This effectively communicates abundance and the reality of the loss of a tremendous number of physical forms.

In the choir sardine replicas hang suspended, illuminated by the projectors. The video causes the sardines’ shadows seemingly to fluctuate – a swish of a tail here, a flicker of motion there, as though they are re-animated. Sometimes video catches in the net and on the facsimiles, presenting an aquarium-like space populated by phantom fish. Re-animation is a theme relevant to several of Wright Cheney’s recent works, most notably evident in Spectre and On the idea of Wilderness. In Spectre, Wright Cheney constructs the form of a polar bear named ‘Buddy’ who resided in a small cage at the Banff Park Museum Zoo in the early 1900s. The ghost of Buddy, constructed out of crocheted snowflakes and crystals, both re-animates the bear in the public’s imagination and draws attention to its life of displacement, just as the snowflakes are displaced and suspended in space. In On the idea of Wilderness the taxidermy form of a cougar is captured wandering New Brunswick, the fabled cougar enlivened through Wright Cheney’s faux-photographic record. I am pleased that Wright Cheney has incorporated video projection into her practice, as I believe this medium has the potential to further ignite her ideas on life, death, loss and the uncanny.

Conversely, because of the way these sardines are illuminated, they exhibit utter stasis and lack of life. In Middle Fork, a recent work by artist John Grade, Grade and hundreds of volunteers reconstructed a Western Hemlock by making plaster casts of the living tree and re-building it with salvaged cedar. The colossal finished piece resembles the Hemlock in its patterns and form, but it lacks that essential spark of life.[1] Wright Cheney’s exploration of the moving image is intriguing in that film exudes life through capturing motion. It is motion that transports the viewer into Sardinia, but there is something truly evocative when motion is juxtaposed with lifeless life-like forms.

Wright Cheney describes to me the process of creating the suspended sardines; she printed out the false skins onto glassine paper and formed the bodies with recycled plastics. She spent many days focusing solely on the manufacturing of these replicas. “I made and made and made sardines, much more than I needed,” she tells me. In this way, she became a one-woman sardine factory, working in an intriguing reverse process from the sardine canneries that were once the lifeblood of Eastport. Rather than take the live fish and put it through the process of washing, cooking, drying and canning, Wright Cheney creates sardine replicas from scratch, conjuring new bodies. “To create a facsimile is to honour the animal,” she says.

Sardinia is a simulated environment, but it is not one that tries to disguise itself as reality. With new technologies, virtual reality and projection mapping, artists can simulate environments to the point of making the real and artificial almost indistinguishable. Sardinia is an easily recognizable falsehood not only in positioning its subject matter above rather than below, but in the sound and light from the projectors, the clearly static suspended sardines and the flat video projection on the opposite wall. I do wish that the edges of the projection be more blurred, that the experience of Sardinia be more immersive and the techniques better veiled. Sometimes I am jolted out of the illusion and distracted by the apparatus. However, if it were a truly convincing simulation – if Wright Cheney had members of the Eastport community spy abundant schools of sardines seemingly shifting in their waters, the piece would potentially be manipulative as a “smoke and mirrors” deception.

It can be problematic when an artist descends upon a community and creates a work that engages with that community’s specific experience – the outsider intervenes and imposes their perspective on a place that has been deemed vulnerable. However, the narrative that Wright Cheney explores here is not only of local but of global concern, though its impact is of course felt to varying degrees. It is also tied to Wright Cheney in sense of place. The last sardine cannery in North America is located in Blacks Harbor, New Brunswick and the history of the sardine industry is deeply intertwined between Maine and Atlantic Canada. The narrative is also meaningful to Atlantic Canadians in relation to the decline of Cod and Atlantic Salmon, and resonates globally with ongoing problems of wildlife loss and rapid species extinction. This communal loss resonates in the infrastructures that remain, (such as the Seal Cove Smoked Herring Stands on Grand Manan Island), in economic, social and political narratives, in the memories and stories of communities, and in the ongoing relationship between humans, ecosystems and wilderness. Sardinia actively engages with this loss, but rather than implicate or lecture, Wright Cheney invites the viewer to enter an intimate world where massive schools of sardines still swim in Eastport.

It is an invention, an event that conjures abundant sardines back, not in the way that they existed before, but as an imagined re-enactment of the past and as an alternate present. Eclipse, a recent piece by Susannah Sayler and Edward Morris on display at MASS MoCA combines video, sound and text to depict the extinction of the passenger pigeon, once the most abundant bird in North America. Eclipse utilizes similar techniques to Sardinia in portraying an overwhelming population that soars over the viewer’s head. There are historical accounts of passenger pigeons weighing down trees and migrating over cities for hours in cloud-like flocks, not dissimilar to schools of sardines. Witnessing enormous schools of sardines is no longer a possible experience in Eastport, but it is one that exists in the psyche of its community. This is perhaps how sardines once moved in this place, how the water was once animated by their shimmering bodies. After experiencing Sardinia, an Eastport resident tells Wright Cheney a second-hand account of spotting from the air a school of sardines that was reportedly 35 miles long and 7 miles wide in the 1940s. There are archives of historical photographs of Eastport fishermen, canneries, and cannery workers available online. The Tides’ Hugh French describes to us how bells used to ring out in the town to call waves of workers to the canneries. Upon entering Kilby House Inn B&B, we pause to notice the fancy porcelain sardine tin that sits as an antique on the table. In this way, Sardinia is a manifestation of collective memory and imagination.

The church setting works well in positioning the viewer; a church suits the contemplation of the infinite and of the afterlife. Wright Cheney tells me that she was inspired by Giotto’s Scrovegni Chapel, where he depicted Heaven on the vaulted ceiling. A church is a gathering place where communities congregate in shared faith and with shared interest, aligning well with the contemplation of large-scale issues that are felt by all. The Free Will North Church is still under renovation, so the space acts more as a frame for the piece than as a designated place of worship. The height of the ceiling and the strength of the atmospheric, often muffled sound piece submerges the viewer into a submarine-like vessel. The very act of gazing upward is a humbling position; we are used to being in awe when we gaze up – at the cosmos, at immense man-made structures, at mountains and at Western Hemlocks, and at art.

This sense of awe and child-like mystification is crucial to the effectiveness of Sardinia. The fish sometimes scatter playfully and move in synchronized and chaotic flux that is a joy to witness. The sound piece lends much to the haunting and calming atmosphere, morphing from dark, ominous tones to light surges. Video and sound are not synchronized, but the viewer experiences magical moments when movement and sound spontaneously swell together. I wonder at points whether the experience as a whole would be stronger with more natural sound – the muffled and heavy silence of being submerged underwater. There are moments when the organ becomes too evident, pulling the viewer out of the illusion and back into the church. However, as a whole the sound piece creates a mood and helps to sway the viewer, reinforcing the cosmic and otherworldly experience.

This sense of awe and child-like mystification is crucial to the effectiveness of Sardinia. The fish sometimes scatter playfully and move in synchronized and chaotic flux that is a joy to witness. The sound piece lends much to the haunting and calming atmosphere, morphing from dark, ominous tones to light surges. Video and sound are not synchronized, but the viewer experiences magical moments when movement and sound spontaneously swell together. I wonder at points whether the experience as a whole would be stronger with more natural sound – the muffled and heavy silence of being submerged underwater. There are moments when the organ becomes too evident, pulling the viewer out of the illusion and back into the church. However, as a whole the sound piece creates a mood and helps to sway the viewer, reinforcing the cosmic and otherworldly experience.

In Eclipse, the passenger pigeons flood the black sky in a white flame-like surge and gradually disappear, leaving the viewer with an empty darkness in their wake. In Sardinia, the sardines exist for as long as the viewer inhabits the space. They fluctuate, turn into shooting stars, they bob playfully in the water. They are encapsulated in Wright Cheney’s place, the church turned submerged vessel and time-space portal. Once the viewer leaves Sardinia, those massive schools of sardines are gone, but there is something that stays behind – an after-image of sorts – the sense of that shifting motion, the ebb and flow of water and fish bodies, the swirl of light overhead.

Claire Shiplett is a writer, photographer and performance artist based in Fredericton, New Brunswick. She studied at the Slade School of Fine Art in London and at Wellesley College in Massachusetts.

Photos courtesy of Janice Wright Cheney

[1] http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2014/01/the-little-town-that-might/355744/

[2] At the same time, the project has the potential to spur appreciation and intimacy that can be crucial to developing meaningful relationships between people and the environment.