TNB founder Walter Learning introduced New Brunswick audiences to a full range of theatre experiences, and ignited his fair share of controversy along the way.

Matt Carter

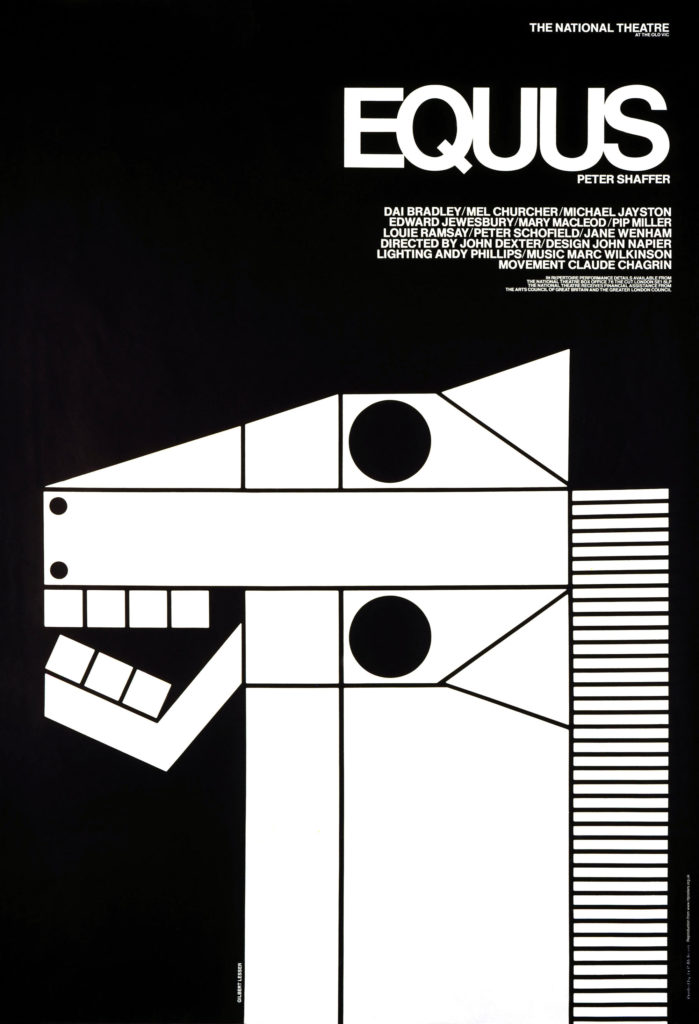

Not long before English playwright Peter Shaffer adapted his 1979 play Amadeus for the silver screen, he wrote another story, one about a psychiatrist and his young patient. With Equus, a play inspired by real-life events involving a 17 year old boy who deliberately blinded six horses on a small farm in southeast England, Shaffer set out to construct a work of fiction in an attempt to explore the possible catalysts behind such a horrific event. The play was a hit. It ran for two seasons at London’s National Theatre before moving to Broadway where it received over 1200 performances with such notable actors as Anthony Hopkins, Leonard Nimoy and Anthony Perkins playing the role of Dr. Martin Dysart.

A screen adaptation of the play debuted in 1977 earning actor Richard Burton a Golden Globe Award for Best Actor in a Motion Picture Drama. By this time, Equus was already making the rounds of theatres large and small throughout Europe, Canada and the United States. It had become as close to a household name as any work of modern theatre could have hoped.

By the time the dust began to settle around the play’s initial impact, Shaffer, in England, was well into his next script. At the same time, on the opposite side of the Atlantic Ocean, a particularly inspired theatre director was plotting a new season for the company he founded nearly a decade earlier. Having read much about the success of Equus in the years previous, Walter Learning decided it would be a perfect fit for New Brunswick audiences and a wonderful way to conclude his ninth season at Theatre New Brunswick.

“It was a great play and it had had great international success over the previous couple of years,” Learning said.

The year was 1977 and by this time Theatre New Brunswick had grown to become one of the province’s most esteemed performing arts institutions with multiple large scale productions touring every season. Its subscription base was in the thousands and it wasn’t unheard of for a single production to be enjoyed by more than 10,000 New Brunswickers. Even the most active professional arts organizations operating in the province today would practically kill for the attendance Theatre New Brunswick regularly enjoyed through the 1970s and 1980s. It was a different time.

“My only concern about that play was that the word fuck was said on stage.”

It was also a very conservative time and Learning was well aware of what he could expect from his audience and what they expected of him. Pushing the artistic envelope wasn’t a priority, although that didn’t stop him from occasionally testing the limits of the ticket buying public.

“In 1973, I did the first Canadian play at Theatre New Brunswick and that was David French’s Leaving Home,” said Learning. “My only concern about that play was that the word fuck was said on stage.”

“In 1973, I did the first Canadian play at Theatre New Brunswick and that was David French’s Leaving Home,” said Learning. “My only concern about that play was that the word fuck was said on stage.”

Few audiences today would be offended or even surprised to hear cursing on stage. It’s funny to think that in 1973, a time when drive-in theatres showed soft core adult films on certain nights of the week, that anyone would be offended by the course language, but there you have it. Again, it was a different time.

By this time, TNB had established audiences in as many as twelve communities throughout New Brunswick. And Learning, who had a real knack for landing substantial donations and in-kind support from local service organizations in most of these communities, knew the limits of his audience.

“I started thinking about where we were going to get hit and who would be upset by the language in Leaving Home,” said Learning. “I figured we’d get hit in Woodstock and in Sussex because that’s where the Bible Belt was at the time.

“At first I wondered if we should change the word. I read the play, and reread it, and reread it again and the word comes out when the father in the story is beating his son with a belt and the son says, ‘never fucking hit me again.’ Eventually I decided we wouldn’t change it because there was nothing gratuitous about it. The word comes out of an absolute necessity in the moment and I felt if required, I could defend it, no trouble,” he said.

Leaving Home toured the province, stirring up just enough controversy to be a helpful act of marketing. Gossip and curiosity are sometimes great friends.

“We go off and we do the tour. It sells out everywhere,” said Learning. “There were also protests everywhere. The biggest one was in Saint John in front of the high school and there were hundreds of Baptists there from the Full Gospel Assembly who back then occupied the building that is now the Imperial Theatre. They tried to get the school boards to deny us access to the theatres but thankfully we had contracts.

“So we did the tour and believe it or not, all the fuss was not about the use of the word fuck. These religious groups were more upset about the blasphemies. The ‘Jesus Christs’ and the ‘Oh My Gods’. Not one negative comment was about the F-word,” said Learning.

“…the most significant contemporary play TNB has produced.”

On another occasion TNB produced a play that involved actors gutting freshly caught fish live on stage. But cleaning fish was one thing, people did that all the time. Audiences, especially those from the Maritimes, could relate to such a task far more than they could to something like full-frontal nudity, which was exactly what Learning would deliver when Equus hit the Playhouse stage on October 17, 1977. The company’s production would erupted into a full blown provincial controversy that played out through the papers, though letters to the editor and through stacks of letters received by the theatre addressed to Learning directly.

While TNB’s production of Equus received rave reviews from those in attendance, others reacted passionately without ever seeing a performance. The idea that one of the province’s leading flagship arts organizations would purposefully expose its own audience and the good people of New Brunswick to nudity was completely unheard of.

Telegraph Journal newspaper reporter Jo Ann Claus attended the show’s dress rehearsal and wrote a glowing review for the paper’s October 17 edition which hit the stands hours before opening night. In her piece, she described the controversial nude scene as being, “so natural, so honest and so sad that the audience watched in quiet sympathy,” and closed her feature by calling the play, “the most significant contemporary play TNB has produced.”

Ralph Costello was also in the audience that night. Costello, who was the publisher of the Telegraph Journal at the time, is the person Learning credits for creating the controversy that blew up around the production.

“Equus really got people stirred up thanks to Ralph Costello,” said Learning. “What a guy. Ralph was the editor of the Telegraph Journal and Alden [Nowlan] was a regular columnist at that time. Ralph had come up to Fredericton for business and he was staying at the Beaverbrook (now the Crowne Plaza Fredericton) on the night of our preview performance.

“Ralph was astounded. He phoned Alden the next day and said, ‘do you know what’s going on up here?’ He wrote an editorial that appeared in the paper and in it he asked something along the lines of ‘is Learning single handedly lowering the morals of the people of New Brunswick?’

“He really stirred the pot and I give him credit for that show selling out,” said Learning. “You couldn’t buy the attention he brought to the play.”

As the production went on, the letters continued to flooded in. Concerned citizens and church groups accounted for the lion’s share of mail that filled the TNB mailbox and occupied space in the letters to the editor section of both the Telegraph Journal and The Daily Gleaner for the entire duration of the play’s Fredericton run and the two week tour of the province that followed.

For some, it seemed as though Satan himself had taken the reins of this once reputable theatre company. Here are three actual letters written by concerned Fredericton residents:

One woman has said in her article that the nude scene in Equus lasted only a few minutes in a two-and-one-half hour performance. Satan is very cunning and crafty. In the next play the nude scene will last longer and so on and so on until the public will become so accustomed to it no one will be shocked any more. On Monday night I saw the Barber of Seville. It was a delightful performance. The House was packed. I am sure by the applause everyone enjoyed it. Why can’t we have more shows like this, in the theatre, on stage and on T.V.? – Christine Holroyd. Fredericton

I myself did not see the play nor would I want to. Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden covered themselves with fig leaves when they realized they were naked, and God made them coats of skin. From that time onward men were meant to keep their bodies covered. We are taught that women should “adorn themselves in modest apparel.” There is no modesty in nakedness. – Mrs. R. Mills. Fredericton

Let’s take time to write and show concern against the recent pollution in our city, pollution of the worst kind. I’m referring to the play Equus. If we care enough for our city, our province, our neighbours, our children, we must take time to speak out now before it is too late. Displaying the human body naked is not modern art, it is shameful, sinful and immoral. If God our Creator thought our bodies were modern art, why did he clothe Adam and Eve? What right does this Playhouse have to show naked bodies? As far as I’m concerned, it’s all for more money. Please people, don’t put money first, people come first always. Look what is happening to some of our beautiful children. They are suffering because many adults put money first. We love people young and old, we want our nice clean city to stay clean. How about you? – A Mother, Fredericton

The play’s Fredericton run welcomed close to 5000 patrons and according to Learning, resulted in only one complaint from a patron who apparently missed the Mature Content warning posted in the Playhouse lobby, and their only objection was that they had not been forewarned.

The provincial tour of Equus included stops at many New Brunswick high school theatres including Saint John High School. Prior to the tour’s arrival, a petition had been circulated throughout the city calling for a ban on the planned performance. When Learning heard about the petition and the 1300 signatures it had generated some days in advance of the show, he simply replied, “We’ve pre-sold 1800 tickets. That’s our petition from people who want to see the play.”

The production also raised concerns about the use of school theatres as a venue for such displays of apparent moral decay. In his November 2 letter to the editor of the Telegraph Journal entitled School Boards Should Stop Exhibitions of this Sort, William French, a concerned teacher from Belleisle Creek, New Brunswick called for all New Brunswickers to, “take stock of what is now happening, the public displays of indecency and the foul language in the TNB plays. Let us let our school board members know that we want to close the door to such offensive and degrading productions as Equus, now being popularized.”

“The biggest advice I wanted to get through was to never mistake an apparent lack of sophistication for a lack of insight and intelligence. This audience has seen a range of plays from the classics to the most modern and the newest. They’ve seen their Shakespeare, they’ve seen their Sheridan, they’ve seen their Miller and they’ve seen Tennessee Williams. They know their theatre.”

Looking back at what Learning was able to accomplish in those early days of Theatre New Brunswick, the cursing and nudity are all but forgotten, buried beneath a wealth of inspiring experiences and performances delivered to a large portion of rural and urban New Brunswick audiences. Possibly his greatest accomplishment in TNB’s first decade was the simple act of touring. By bringing popular works of theatre to audiences all over New Brunswick, Learning was indeed instrumental in fostering the culture of theatre that now exists in all corners of the province.

“We welcomed actors from all over Canada,” said Learning. “And I would tell them that when they go on tour they will meet an incredible range of audiences. They’ll be invited into people’s homes and receive some wonderful hospitality. But the biggest advice I wanted to get through was to never mistake an apparent lack of sophistication for a lack of insight and intelligence. This audience has seen a range of plays from the classics to the most modern and the newest. They’ve seen their Shakespeare, they’ve seen their Sheridan, they’ve seen their Miller and they’ve seen Tennessee Williams. They know their theatre.

“The actors would always come off the tour amazed,” he said.

“There remains a void that only the communal experience of watching something unfold on stage can fill.”

Learning announced his departure from TNB in 1978, ending his first of two stints with the company. One of his final acts as Artistic Director was to join the company on tour and visit each of the twelve tour communities and personally thank the audiences for their support.

“I went out on the last tour to say goodbye to everyone,” said Learning, “and in Sussex I remember a farmer in his sixties came up to me and said, ‘Mr. Learning, I just want to thank you. One of your plays changed my life.’ He told me it was, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Wolfe. I thought, what in the name of God was happening in that man’s life eight years ago that would make this play have such an impact. It was just astounding. It’s the old throw the pebble into the water and watch the waves just go and go and go. You have no idea who you’re affecting but you know it’s happening.

“That hunger was there then and I think that hunger is there now,” he said. “There remains a void that only the communal experience of watching something unfold on stage can fill. There’s nothing else that does what that does. Nothing.”

Walter Learning died January 5, 2020 after a lengthy illness.